In OpenSees (and any other finite element software), equation numbering is a quiet, behind the scenes analysis option that users do not have to pay any mind. No matter how a user numbers the nodes in their model, e.g., for bookkeeping or from a mesh generator, the equation numberer will clean up any messes.

But what if you wanted to know the sequence of nodes traversed by the equation numberer in an OpenSees model? This information can be useful for matrix visualization, model debugging, and understanding how equation numberers work.

Equation Numberers in OpenSees

Equation numberers operate on nodal connectivity, not on the actual stiffness matrix topology. All nodal DOFs are assumed to give non-zero contributions to the stiffness matrix, regardless of numerical zeros due to element orientation, or numerical cancellation of stiffness contributions.

The RCM numberer will use a breadth first search of a model’s nodal connectivity graph to assign equation numbers that will reduce the stiffness matrix bandwidth while the AMD numberer will use approximate minimum degree ordering to reduce fill-in during sparse matrix factorization. The Plain numberer will number equations in the order of increasing node tag.

A few additional notes on how OpenSees assigns equation numbers:

- The equation number -1 is assigned to all constrained DOFs in a model

- For a model’s unconstrained DOFs, equation numbers range from 0 to Neqn-1

- All unconstrained DOFs at a node are numbered sequentially before moving on to the next node

Recovering the Numbering Sequence

So, how do we figure out the node sequence used for assigning equation numbers in OpenSees? Sure, we can build a nodal connectivity graph from a model and then call the reverse_cuthill_mckee function from Python’s scipy library, but that approach could give a different ordering than OpenSees due to implementation details for an algorithm with multiple solutions.

Many OpenSees-centric approaches are valid, but a simple solution is to use a dictionary that maps the largest equation number at a node to the tag of that node. Because the numberer assigns equation numbers to all unconstrained DOFs of a node consecutively, the largest equation number is the bread crumb that tells when the numberer visited the node. A mapping of equation number to node tag is preferred (as opposed to tag to equation) because a model’s equation numbers are always sequential while the node tags are arbitrary.

Equation numbers are assigned at the start of an analysis, i.e., you have to call analyze() or eigen() before retrieving equation numbers via the nodeDOFs() function.

import openseespy.opensees as ops

#

# Build your model

#

ops.analyze(1)

eqns = dict()

fixed = []

for nd in ops.getNodeTags():

maxEqn = max(ops.nodeDOFs(nd))

if maxEqn > -1:

eqns[maxEqn] = nd

else:

fixed.append(nd)

p = []

for nd in sorted(eqns.items()):

p.append(nd[1])

print('permutation =',p)

print('fixed nodes =',fixed)

For models that use the Plain or Transformation constraint handler, nodes that have all DOFs constrained will have a maximum equation number of -1. The code above stores these nodes in the fixed list. We have no way of knowing a posteriori where in the numbering sequence a node received all -1 equation numbers for its DOFs. But if a model uses the Penalty or Lagrange constraint handler, the constrained DOFs will have positive equation numbers and you can infer the numbering sequence across all nodes in your model.

Minimal Example

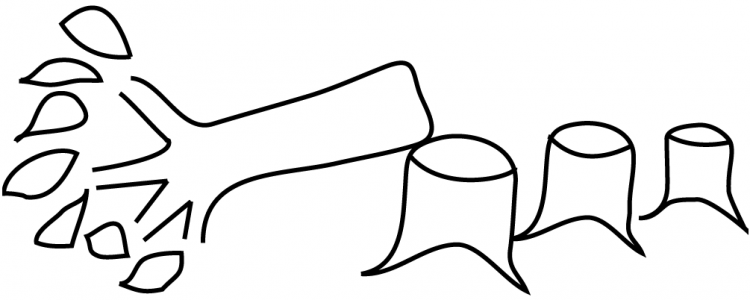

A minimal example will show the recovered node sequence is correct for the default analysis options of Plain constraint handler and the RCM numberer. The beam shown below has five elements with six node tags any Lost fan will recognize.

The RCM equation numberer should override the random ordering of node tags and number the equations across the beam nodes. To model this beam and examine equation numbering, the element lengths and section properties do not matter because this example is all about the nodal connectivity.

ops.wipe()

ops.model('basic','-ndm',2,'-ndf',3)

ops.node(4,0,0); ops.fix(4,1,1,1)

ops.node(42,1,0)

ops.node(15,2,0)

ops.node(16,3,0)

ops.node(23,4,0)

ops.node(8,5,0); ops.fix(8,0,1,0)

ops.geomTransf('Linear',1)

ops.section('Elastic',1,2004,6,108)

ops.element('elasticBeamColumn',1,4,42,1,1)

ops.element('elasticBeamColumn',2,42,15,1,1)

ops.element('elasticBeamColumn',3,15,16,1,1)

ops.element('elasticBeamColumn',4,16,23,1,1)

ops.element('elasticBeamColumn',5,23,8,1,1)

# Default: Plain constraint handler, RCM equation numberer

ops.analysis('Static','-noWarnings')

Running this model through the code to recover the equation numbering sequence gives the following results:

permutation = [8, 23, 16, 15, 42]

fixed nodes = [4]

As expected, the RCM numberer runs across the beam numbering nodes in the connected sequence, in this case from right to left. In addition, the completely fixed node is detected and noted in the output.

For this simple model, the AMD numberer will give the same sequence as RCM and the Plain numberer will return [8,15,16,23,42] based on increasing node tag.

Limitations

A couple of limiting edge cases with this approach:

- If your model uses

equalDOFconstraints, thePlainconstraint handler (the default handler) will assign the same equation number to the affected DOFs of the retained and constrained nodes. Identical equation numbers at multiple nodes could lead to an incorrect inference of the node sequence using the code above and some adjustments will be necessary. - Multi-point constraints like

rigidDiaphragmorrigidLinkalter the nodal connectivity. As a result, the node sequence can differ based on which constraint handler you use. TheTransformationconstraint handler removes equations andLagrangeadds equations, whilePenaltydoes not alter the number of equations.

As usual with topics related to constraint handlers and equation numberers in OpenSees, the what-ifs pile up quickly. But this post provides a starting point if you would like to know what sequence of nodes the numberers traverse in your models.

One thought on “Reverse Engineering the Equation Numberer”